Inside AWiM25 at the African Union: Scheherazade Safla on Gender,

Trending

Friday March 6, 2026

Trending

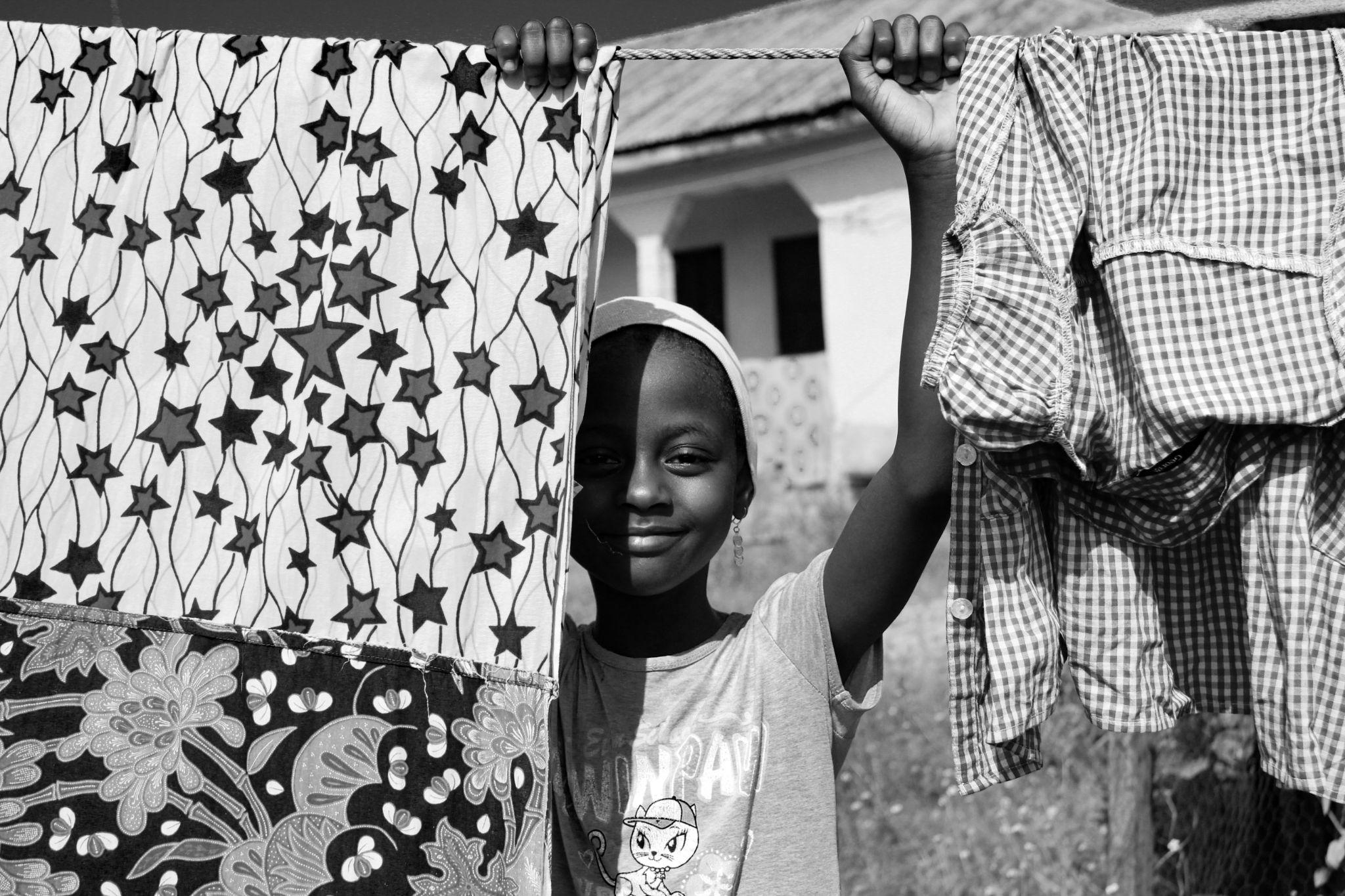

Photo Credit: Muhammad-Taha Ibrahim on Unsplash

Scholastica Naliaka, now 14, from Busia County, Kenya, suffered a devastating experience of sexual abuse at the hands of a well known neighbor when she was just 12 years old. The perpetrator, a record keeper at a local health facility, assaulted her on her way home from school, threatening her with death if she spoke out and bribing her with money to stay silent. Months later, Scholastica’s father, Odhiambo Richard, discovered the truth when he noticed signs of pregnancy.

“I could not understand how it happened and when I asked her who was responsible, she only cried and ran away saying she did not want to die,” says Odhiambo.

He knew his daughter had been defiled and moved to know who had done it. He therefore involved his entire family to get the girl to talk and that was when she broke the news that she had been defiled and the perpetrator had threatened her.

He went to report at the nearest police station in Butula subcounty where he was asked to take the girl to the hospital to have the Post Rape Care form filled.

“Even after taking the case to court, I feel justice for my daughter has been delayed because the case has been postponed severally and it seems the perpetrator is interfering with it,” says Odhiambo.

In one instance he said the case was postponed because the perpetrator was unwell, yet according to him, he had seen him in the village bragging that nothing could be done and that he was a free man. In another instance, the case was postponed because the perpetrator’s lawyer had another case he was presenting in court.

He then wrote a letter to the Chief Justice to have his case moved to another court or get handled by another magistrate.

“He tried to threaten me when he heard we had reported the case to the police, he told me he would support me raising the child but when I refused, he said he would deal with me, so I am living in fear, maybe he will one day attack me and harm me or the child,’ narrates Naliaka.

Naliaka gave birth and was transferred from her school due to the stigma from her schoolmates.

The highest rates of child sexual abuse in Africa are reported in Morocco, Tanzania and South Africa. However, the majority of the cases are not known by official agencies.

In Nigeria, 47 per cent of female child labourers reported being sexually assaulted, in Ghana, transactional sex and children watching pornographic images were the most prevalent forms of sexual abuse.

According to the World Health Organization, nearly 3 in 4 children –300 million children aged 2-4 years regularly suffer physical punishment or psychological violence at the hands of parents or caregivers.

Also, one in 5 women and one in 13 men report having been sexually abused as a child aged 0-17 years.

Additionally, WHO reports that 120 million girls and young women under 20 years of age have suffered some form of forced sexual contact.

Despite her parents’ support in caring for her child, Naliaka’s academic performance has significantly declined. She faces additional challenges at school, where peers constantly taunt her with hurtful names, such as ‘mother’ and ‘old man’s wife.’ The relentless bullying has led to social isolation, making it difficult for her to connect with classmate.

Rono Kemei from Teso Ward is a sad father. His daughter was defiled by a farm hand working in their Member of County Area’s home (MCA). He narrates that the MCA’s wife found him defiling the 7-year-old girl in a store in the family house and he quickly apologised.

Photo Credit: Rose Mukonyo for AWiMNews

“My daughter had visited the MCA’s home because we are cousins and she liked playing with his children. She found them watching television in the living room and when the farmhand saw her, he called her into the kitchen but instead pulled her into a store where he defiled her,” he says.

When the wife of the MCA reported the incident to the authorities, she was asked to take the girl to the hospital but before she did, she helped the worker escape.

All this while, Rono says they had not informed him or his family of what had transpired until his eldest daughter overheard people talking in the village market.

He followed it up by going to the MCA’s home and that was when the daughter was brought back, with medical forms that showed she had been defiled and needed further tests and medical attention.

“The doctor who attended to her complained that she was supposed to have been taken back for further medical attention and to get the recommended preventive medicine but it was intentionally delayed. I just pray he testifies in court because I am worried about my daughter’s health since it seems like someone intentionally delayed this,” he laments.

After the case was taken to court, the MCA began to threaten him with death after asking him to withdraw the case and he declined. He even offered him money and suggested he would educate the girl. However, Rono has vowed not to bow to pressure and is willing to pursue the case to ensure his daughter gets justice.

“It may seem unreal seeing fathers standing up for their daughters because this was not the case previously, and I will make sure my daughter gets justice even if I pay for it with my own life,” says Rono.

Mary Makokha, the founder of the Rural Education and Economic Enhancement Programme (REEP) based in Busia County, has been dealing with the protection of women and girls from sexual and gender-based violence.

She reveals that the most disturbing cases in the area involve incest, where family members prey on vulnerable children. This includes fathers exploiting their daughters, uncles abusing their nieces, or grandparents violating their grandchildren’s trust. Alarmingly, most perpetrators are individuals known and trusted by the victims

Photo Credit: The REEP website

She explains that culturally, those families will only hold out of court agreements where a goat is slaughtered to cleanse the family and also if any child is born out of incest they are usually killed. The defiled girl is never taken to the hospital.

Makokha notes that previously, the Luhya culture undervalued girls, leading to a disturbing trend. In cases of defilement, parents often prioritized financial compensation from the perpetrator over seeking justice for their daughters

“You would hear of statements like, ‘If you do not give me Shs 200,000 (approximately $1,500)) or a cow then I will take this case to court,’ and when you are following up a court case and suddenly begin seeing the perpetrator’s family selling cows or land, just know the survivor’s family has been compromised and the case will collapse,” explains Makokha.

According to her, men would interfere with the cases of defilement because Busia is largely a patriarchal society and the men would be paid to stop the women from pursuing the cases.

By creating awareness in the communities on the importance of getting justice and protecting the girls, the REEP organisation has brought more men on board and formed the men’s champions group. This has also been done in at least ten schools, where boys’ clubs were formed that empowered boys to protect girls. REEP has also been organising psychological counselling for the survivors and their families.

“I have seen girls develop very loose morals because she was defiled and lost their self-worth, girls grow up hating men, and others dying by suicide because they suddenly discovered that the drugs they have been taking are ARVs and that they were infected with HIV through a defilement,” says Makokha.

Makokha explains that the children and their guardians need counselling because according to her, some parents are helped to accept their children after defilement as some may blame them for exposing themselves to the perpetrators. Some parents are overcome with guilt for believing they were not responsible enough.

In line with this, Takia Mzinza, a Psychological Counselor has been helping defilement survivors also added that “When a child is defiled, they are affected psychologically, are confused and remain in a state of shock, so I offer a safe space where the child can process the experience, and that is when I take them through a healing process with coping mechanisms that are age-appropriate,”

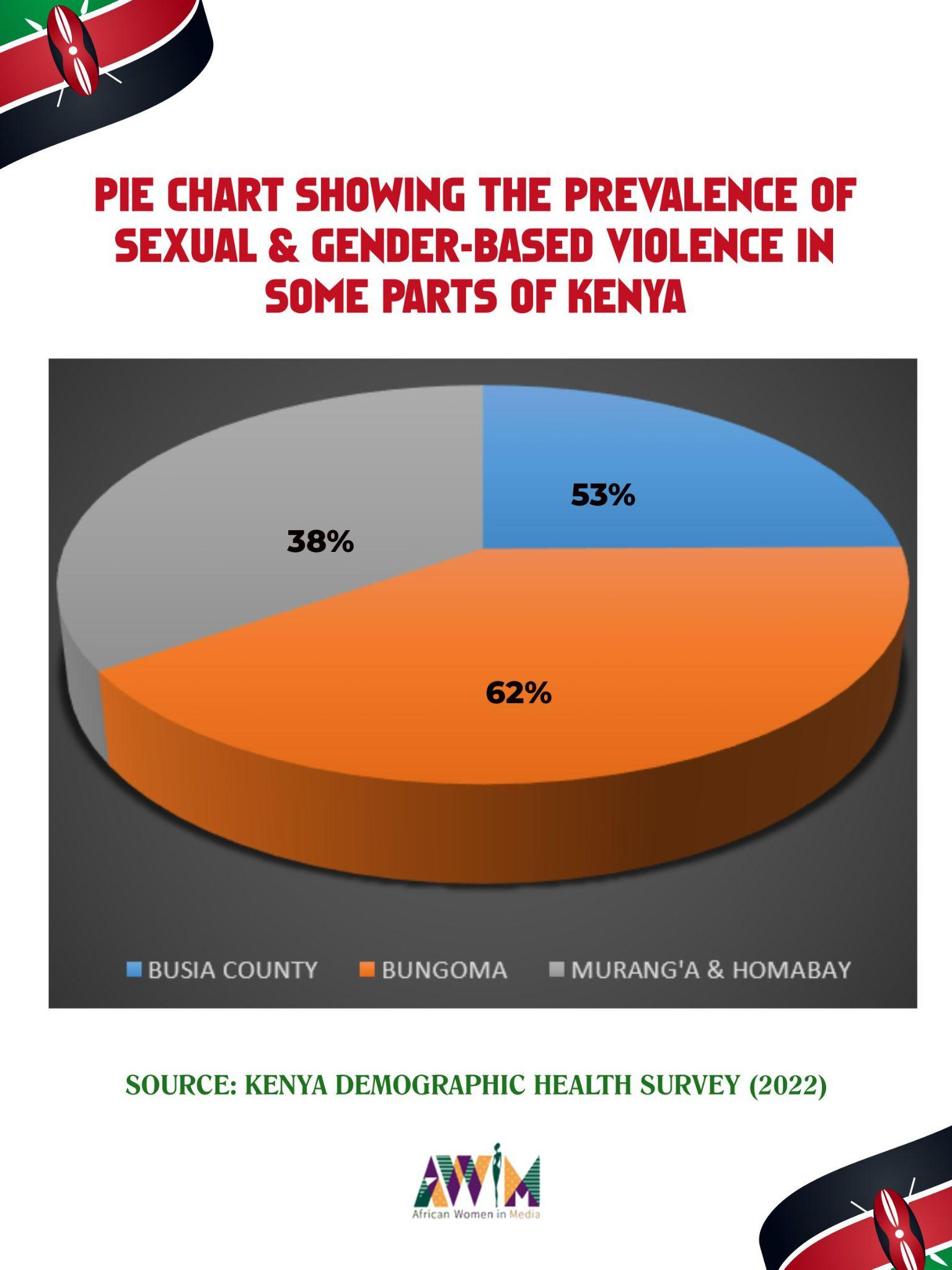

According to Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2022, Busia County has a prevalence of 38 percent of sexual and gender-based violence, with Bungoma leading with 62 per cent, and Murang’a and Homabay at 53 per cent.

Counties in Kenya with the lowest rates of gender-based violence include Kwale and Wajir at 13 and Kitui at 12 per cent

Jeanpaul Murunga, is the Equality Now Programme Officer for Ending Sexual Violence . He says that there has been an increase in the number of defilement cases being reported in Busia which means awareness has been created, but there are some kind of disconnection present in the legal framework and the enforcement of the Sexual Offences Act of 2006.

Jeanpaul Murunga, Equality Now Programme Officer for Ending Sexual Violence

He explains that if the health records are not well captured in the Post Rape Care Form, then they cannot be used as evidence in a court of law and may lead to the collapse of the case.

According to Section 36(3) of the Sexual Offences Act of 2006, a police officer who is on duty who has received a report that a sexual offence has been committed against anyone shall notify a medical practitioner who shall conduct a full medical examination on the victim, prescribe the appropriate treatment and complete the prescribed Post Rape Care form.

This gap is also seen in the urgency with which the police act to preserve evidence by ensuring the right details are captured and presented in court.

THE IMPACT OF THE SGBV COURTS IN KENYA

Murunga also states the establishment of these courts is a testament to our resolve to address this deeply rooted issue. They are uniquely designed to handle the delicate nature of GBV-related cases, a much-needed departure from the traditional approach which has often led to re-traumatization of victims. These courts embody a trauma-informed approach that prioritises the victims’ safety, dignity, and privacy.

According to the Busia Alternative Dispute Resolution Committee Chairperson Sheikh Ali Nguu, the committee is not allowed to listen to cases of defilement or murder and that whoever is found doing so is arrested and taken to court.

“It is unfortunate when you hear that the perpetrator has managed to escape and cannot be traced yet the survivor and her family duly reported the incident,” says Ali Nguu

He says anyone found guilty of trying to solve a defilement case out of court is considered an accomplice of the crime hence the abolishment of kangaroo courts where the survivor’s family would negotiate with the perpetrator instead of going to court. This has continually reduced the number of defilement cases as ‘would-be’ perpetrators know they will be taken to court and jailed according to the law.

The SGBV Courts are staffed with specially trained judicial officers. These judicial officers have been trained on the intricacies related to SGBV, including survivors’ needs and are equipped to handle the complexities of such cases with utmost sensitivity.

Kenya has rolled out a strategy in these courts which begins operations in hotspot areas including Mombasa, Siaya, and Kisumu counties.

According to Leah Otieno, an advocate and Program Officer at Utu Wetu Trust, SGBV courts were established after it was realised that over time, these cases were being delayed in courts further traumatising the survivors and their families and often times, the perpetrator would go scot-free due to either lack of evidence or how the case is handled.

“The SGBV courts are important because they adopt a trauma- informed approach in assisting survivors of SGBV in Kenya through the conduct of the cases and this move to set aside specific courts to address this offence was informed by these factors including the prevalence of the cases in the country,” she says.

She explains that although the judiciary system in Kenya is faced with challenges of backlog of cases and the limited number of judicial officers handling SGBV cases, these courts need to be upscaled across the country and not just in the areas with high prevalence of SGBV cases.

“They do attend the training but not on a large scale and this needs to be scaled up and I believe this is a step in the right direction to support the survivors of SGBV to ensure they get a fair hearing and that justice is served.

She also advocates for further training of judicial officers handling SGBV cases on how to conduct trauma- informed, survivor – centred approaches to SGBV cases.

Editor’s Note: The names of the survivors have been altered in this report for their security.

“African Women in Media’s Gender Stories Editorial Fellowship, supported by Fojo Media Institute”

We’re not gonna spam. We’ll try at least.

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Recent Comments