Inside AWiM25 at the African Union: Scheherazade Safla on Gender,

Trending

Friday March 6, 2026

Trending

Culton Scovia Nakamya, a reporter at BBS Television in Uganda, was the only female journalist on Robert “Bobi Wine” Kyagulanyi’s campaign trail. On Wednesday, December 30, 2020, she joined Kyagulanyi, the main opposition candidate for the January 2021 election, who was heading to Kalangala, a tourist district that is part of the popular Ssese Islands.

Nakamya was looking forward to visiting the island for the first time and getting to experience its much-touted beauty as she worked. From Entebbe, the entourage made its way to the port where they would board the ferry to Kalangala on the tip of Bugala Island, the second-largest on Lake Victoria.

The sight of anti-riot police did not perturb her. Like shadows, they were common features on Kyagulanyi’s campaign, following him wherever he went and firing off teargas that journalists covering the campaign had gotten used to. Seeing counter-terrorism police and the military join them on the morning of the trip, however, dampened her spirits. It was not going to be a “normal” day.

“Before we boarded the ferry, I realised there was a difference in security deployment. It made me nervous,” she said.

At the Ssesse Islands, Kyagulanyi’s team planned to drop by the different campaign spots they had mapped. The media split into two teams to fit into the few available speed boats. One team sailed off with Kyagulanyi, while the other remained on the island. As the team on the island set off to meet the people, the military swooped in, arresting the entire campaign team, including Kyagulanyi’s private guards. Only his lawyer, Mathias Mpuuga, was not arrested.

As journalists clicked their cameras to document the events, masked military police officers who were manning roadblocks shouted: What are you doing here? There is no work for you to do here. Go to your work stations.

“We were not ones to leave without the story, but we could not record anything freely, so we stole photos from side mirrors,” Nakamya told AWiM News.

A military helicopter landed at a distance, and locals intimated to the journalists that it had delivered three plane-loads of heavily-armed soldiers. The journalists pitched camp, waiting to see who would be ferried off in the chopper later that day.

Mbidde called his client to inform him that the team had been arrested, and Kyagulanyi cut short his campaign, and headed back to Kalangala. There, he too was bundled into a police van that sped off towards the parked chopper.

Nakamya live-tweeted events as they unfolded and took notes on her phone, as her colleagues clicked their cameras to capture every shot. The journalists made way to the van holding Kyagulanyi, where five masked soldiers singled out Nakamya.

“I was taking notes on my phone, updating the digital desk and updating my social media handles. I also recorded video as police fired teargas and live bullets. Then the military men came and picked me up.

“They asked me: Who are you? I knew they knew who I was, but I told them that I was a journalist and identified myself. Then they asked me: Why are you making our work difficult? Why do you say the candidate has been arrested?”

Nakamya responded that the candidate was not free. The army men told her to delete her tweets, and she told them that she had no control over what the station had posted.

Next to her, stood one of Kyagulanyi’s campaign team members in handcuffs.

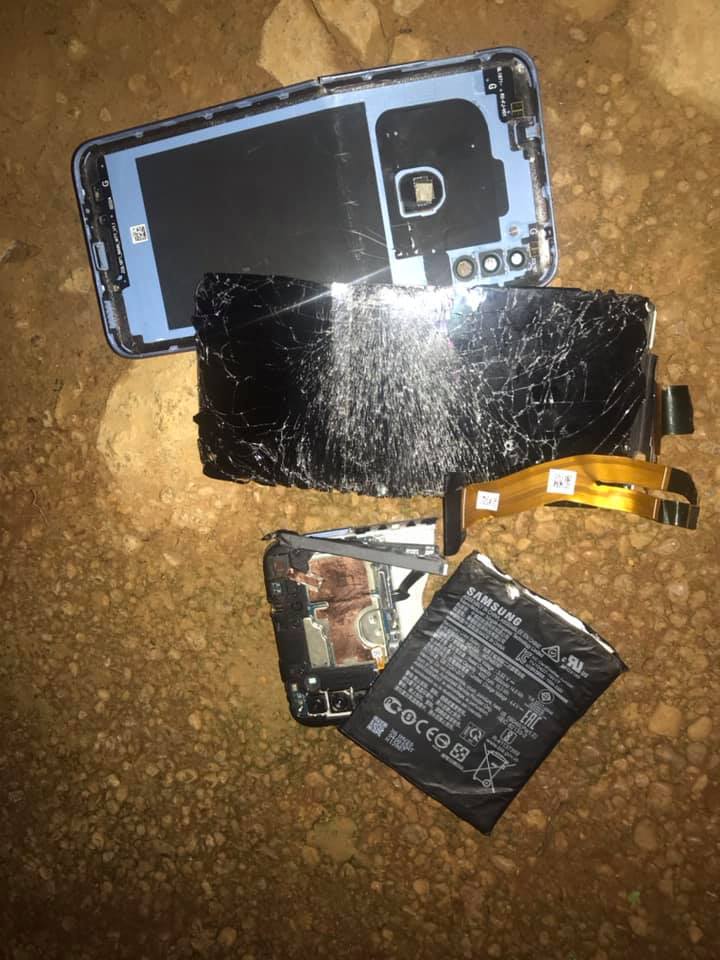

“I thought they were going to handcuff me and I tweeted that I had been arrested. That was my only chance to make noise about it. I knew they would crush my phone because they had just asked another journalist to smash his phone for ‘profiling the masked soldiers.’ I knew the same fate would befall me, so I switched off my phone,” said Nakamya.

As the soldiers were questioning her, they received a call. The caller said: “You have arrested a journalist!”

Out of fear of the uproar that would follow, now that word of a journalist’s arrest was out, the soldiers let her go. On the sidelines, members of the public who had gathered, chanted: “Release Nakamya.”

Her colleagues were silent, fearing that if they joined in, they too would be picked up and harassed. While the army allowed her to join her colleagues, the ordeal was far from over. Seven heavily-armed soldiers with intimidating looks circled the journalists for half an hour.

“They said nothing to us, but we couldn’t move a finger or look at each other. We stood still, fearing the worst – with their fingers on their triggers, it appeared as if they were waiting for an order to shoot us,” she recalled.

Phones rung endlessly without being received. Cameramen no longer risked stealing a shot.

“We appeared strong on the surface, but deep down we were terrified.”

As the journalists were detained, Kyagulanyi was put in the chopper and flown off. The crowd that had gathered had long been dispersed, and the reporters were not allowed to take a peek at the helicopter as it flew off. Once the vessel was out of sight, the mean-looking soldiers asked the journalists: Why aren’t you doing your work?

They were now free to leave; they boarded their vans to the ferry landing and crossed back to Entebbe.

“We were scared and traumatised. Upon reaching the shore, we hugged and heaved a sigh of relief: We were safe!”

It’s been three months since the hotly-contested, violent and disputed election, and Nakamya says she has lessons for next time.

“I would still cover elections again, because I have to tell the story, but I would change the way I work. No story is worth my life; I shouldn’t have to choose between death and the story. We have families and people who care about us, so as much as I would still cover elections, I would not risk my life like that again.

Nakamya also says that media houses should train journalists to prepare them for such assignments, and buy them gadgets and protective gear. She adds that media houses should have psychologists on call to debrief and counsel journalists who experience trauma in the course of their work.

The journalist recalls the terror she felt while reporting live at the National Tallying Centre, where results were being announced.

“The hail of bullets and teargas explosions on the campaign trail still echoed in my mind and ears, and a spark of electricity sent me into a spiral of trauma,” she said.

“I was reporting live, but that spark made me jump and I nearly ran off. I didn’t realise how much the violence and harassment had affected me, until that day. Just an electric spark and I was back to the terror of the campaign trail.

“I am disappointed because no media house provided psychosocial support for journalists. I asked my colleagues and none have received help. They (media houses) think that because we are walking, eating and talking, we are okay; that we have moved on. We are not okay. Sometimes you ask for a break and they say no. They think we are very strong. They think we are special because we faced all this and ‘survived’, but deep down, we are traumatised,” said Nakamya.

Irene Abalo, a Daily Monitor reporter, who covered Gen Mugisha Muntu, another opposition leader, says that while things were not as tough as in Kyagulanyi’s National Unity Platform camp, the journalists still lived on edge. She covered the campaign with another female journalist, while the rest of the team were men.

“Most women are mothers and breadwinners, hence the decision by editors to protect them from hostile fields. Your children, husband, mother or father watch other journalists being shot at or hear as the police call journalists ‘collateral damage’. These are not easy events for them because they care about our wellbeing. We have to be cautious because no story is worth a journalist’s life,” she told AWiM News.

We’re not gonna spam. We’ll try at least.

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Recent Comments