Groundbreaking Workshop on AI and Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence at AWiM24

Trending

Sunday June 1, 2025

Trending

Earlier in January, Zainab Adams was shortlisted alongside 23 other female journalism students to attend a workshop on digital rights and gender-based violence reporting organised by a Non-Profit Organisation, Education as Vaccine (EVA) in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. She didn’t know that the knowledge she would gain during the workshop will one day come in handy for the benefit of other youths.

The two-day workshop was part of a year-long project themed ‘safe to surf’ and aimed at making people understand their rights and responsibilities as digital natives.

The digital space has over the years become the town hall of the 21st-century global village where friendships are built, debates take place, ideas are shared and solutions to social problems are discovered and analysed.

What this means especially with the outbreak of the Coronavirus is that the amount of time people across the world spend online has continued to increase, with an average internet user spending over six hours and 58 minutes online daily.

For too many women, the digital space remains unsafe as a huge volume of gender-based violence takes place on social media, thereby posing a threat to the progress on gender equality.

Women and girls continue to experience increased forms of online gender-based violence, racist and sexist abuse, doxing, and other harms that can violate their rights to free expression, non-discrimination, privacy, and the right to live free from violence.

“I observed that GBV happens everywhere, particularly on social media, yet little attention is paid to it. Survivors get attacked, bullied and they end up blaming themselves or suffering in silence,” Zainab tells AWiM news.

Zainab alongside other female campus journalists from tertiary institutions across Nigeria’s thirty-six states joined the war against gender-based violence using social media campaigns: Twitter spaces, WhatsApp conversations, Instagram & Facebook live conversations as well as a series of posts across social media platforms between 13th to 27th of July this year.

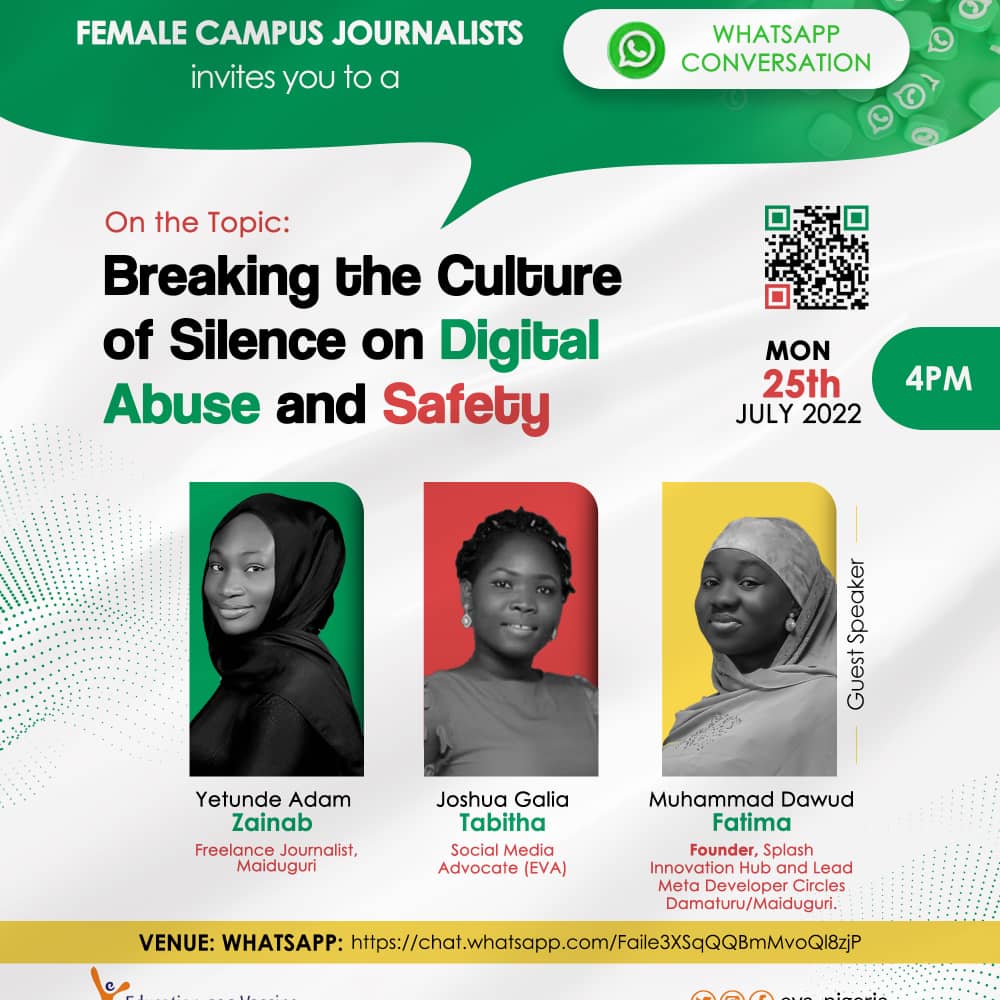

On the 25th of July, Zainab via a WhatsApp group conversation sensitized over 100 young participants on ‘breaking the culture of silence on digital abuse’ with sponsorship by EVA and training assistance from two other colleagues, one a female campus reporter/social media advocate and the other a member of Meta Developer Circles at the University of Maiduguri where she is pursuing a degree in Mass Communication.

“Social media campaign is one of the most efficient media of tackling gender-based violence since the act is mostly perpetuated on social media and mostly affects youths who spend more time online,” Zainab explained.

Findings have shown that around 1 in every 3 women in Africa has experienced some form of online gender-based violence.

Globally, the overall prevalence of online violence against women is 85 per cent, while that in Africa is 90 per cent.

“I’ve once had a total stranger send me an offensive picture on social media as well as other cases of online violence including people stalking me online or making nasty comments about me.” Says Anthonia Umoh, another female campus journalist who utilised Twitter space and Instagram live for her campaign.

Anthonia carried out her campaigns on the 19th and 21st of July together with a fellow female campus journalist, Mary Joseph on the topic, ‘understanding digital gender-based violence’ because to her, many people don’t know these things and it is when people know the digital rights that they can protect themselves from digital abuse.

“I carried out my campaign on Twitter and Instagram because I realized that a lot of things happen on Twitter and people see it as normal but it’s not normal. A lot of sexual harassment happens on Instagram both to me and other women so I wanted people to know their digital rights and how they can protect themselves from people stalking, bullying or trolling them on social media,” she added.

A 2020 study by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) claims that 78 per cent of women are often unaware that options exist to report harmful online behaviours.

Anthonia says her motivation was the drive to create awareness for people that may be going through violations without even knowing they’ve been violated.

For her, social media is the best way to tackle GBV because almost everyone is on the internet now, especially since the lockdown in 2020 which got people accustomed to spending time online without physical contact with other persons.

What Online Gender-based violence means

“If you can’t randomly slap someone at the bus stop for saying something that does not sit well with you, why should you slap them online?”

These words of EVA’s Executive Director, Toyin Chukwudozie during the workshop organised for female journalism students aptly describe the unjustifiable nature of online gender-based violence which has taken hold of our generation.

According to the United Nations, violence against women is defined as: “Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”

Therefore, online gender-based violence is one directed at a person based on their gender or sex using the digital space.

Online gender-based violence is commonly defined as an action facilitated by one or more people that harm others based on their sexual or gender identity or by enforcing harmful gender norms, which is carried out by using the internet or mobile technology. This includes stalking, bullying, sexual harassment, defamation, hate speech and exploitation, or any other online controlling behaviour.

According to a report by Web Foundation, online gender-based violence and abuse threatens to hamper the web’s potential to be a platform that amplifies gender equality and spearheads positive change, and instead cause it to remain one more medium in which women, and particularly women from marginalised communities, are attacked and have their voices suppressed.

Amidst all these, journalists as purveyors of information have a vital role to play in curbing GBV by educating, informing, creating awareness and shaping the opinions of youths and stakeholders through relevant stories.

“Rather than just writing negative stories of people who have suffered gender-based violence, it’s better we just create awareness on the issue so people can avoid them. Anthonia continued.

“Educate people about their digital rights and gender-based violence so that they know that what they go through is not normal and doesn’t have to be normal. They need to know it is wrong because it is when you know that something is wrong that you consider standing up against it.” She concluded.

This article is part of the African Women in Media (AWIM) Graduate Trainee Programme in collaboration with Fojo Media Institute

We’re not gonna spam. We’ll try at least.

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Recent Comments