Groundbreaking Workshop on AI and Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence at AWiM24

Trending

Monday June 2, 2025

Trending

I arrive for the Friday afternoon appointment with Eunice Omollo right on time. Eunice, a health and science journalist at the Nation Media Group in Kenya, has been hesitant to share her story, but when we set up this interview, she assured me she was ready.

There is no sign of Eunice, and after a few minutes of waiting, I wonder: Has she backed out?

Half an hour later, she walks in clutching a blue handbag, a broad smile on her face. Her five-year-old son fought with a classmate over an insult, and she went to his school to resolve it, before making her way here. After pleasantries, she dives right into the conversation.

“I always come up with an excuse when someone wants to talk about my mental health. I don’t know how I agreed to this interview … but, it’s okay; we can go ahead,” she says.

With six years of reporting under her belt, Eunice has become the go-to person for health-related stories in the newsroom. In addition to general health and science news, she has a soft spot for stories on sexual and reproductive health, maternal health and HIV.

“The more I report on health, the more I learn. My colleagues call me Mama Afya, loosely translated as mother of health,” Eunice told AWiM News.

It came as no surprise when Eunice was awarded best health reporter in Africa, during the Africa Media Health Network Awards 2019, TV category, in Kigali, Rwanda. And when the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 began to spread rapidly around the world, she was among the first journalists in Kenya to break the news.

“In December 2019, I kept posting about this new virus in our office WhatsApp group, but no one paid attention. The more I posted, the more irritated my colleagues became. The virus reported in China seemed so far off,” she said.

However, her workmates’ apathy did not deter Eunice. She got used to being ignored when she talked about the novel coronavirus, but she kept tabs on it. She stayed up late reading anything she could find on the pneumonia-like virus that did not have a name at the time. It’s only when the virus got closer home – the first case reported in South Africa – that colleagues began to pay attention.

“My journey with COVID-19 started when approximately 12 people were reported to have been infected with the virus in China. I monitored COVID-19 before it got a name, before guidelines to prevent it were developed, and before it became a pandemic,” said the health reporter.

As Eunice exerted herself to bring the news to millions of Kenyans, who were now watching every minute of the global pandemic unfold, another disease was creeping up on her. There was no rest for journalists, especially those on the health beat, and fatigue inched closer to burnout each day.

The virus that causes COVID-19 had elicited high research interest, which meant that Eunice spent days and nights devouring new studies and keeping track of the data. There were no more days off; she was always on call to work on one COVID-19 report or other, or to provide the latest updates. Insomnia became a constant.

“They say too much of something is poisonous. I monitored what was happening locally and globally. I stayed up late and reported to work very early. It became an obsession. I ate, drank, slept, and lived COVID-19. At some point I felt like I was running mad,” Eunice told AWiM News.

Soon paranoia set in. Eunice became worried sick about her sister, who worked at a referral hospital, and had been made head of the department that handled patients with COVID-19. Images of her elderly parents who are terminally ill, flashed through her mind. She wanted to protect them from the virus.

“I went out of my way to meet the need for accurate and current news on COVID-19, but it was zapping the life out of me. I lost appetite. I became anxious. I couldn’t sleep. I was perpetually angry, aggressive and irritable,” she said.

“Behind my striving to produce the best reporting was hidden pain. I didn’t realise that I was steadily becoming mentally ill,” she added.

“There is something funny about being a health reporter: You see yourself in other people. Whenever I covered stories of people suffering from mental disorders, I saw myself in them. I bore witness to their getting help, but never sought help for myself. I convinced myself that I was strong.”

As days turned into weeks and months, and as the pandemic raged on, Eunice became withdrawn. Getting out of bed to go to work became a tall order. One day, she was too overwhelmed; she crashed.

“My sister took me to hospital and I started seeing a therapist. I felt like a failure. I thought of suicide. My therapist referred me to a psychiatrist who diagnosed me with five mental disorders, some of which were cumulative,” Eunice told AWiM News.

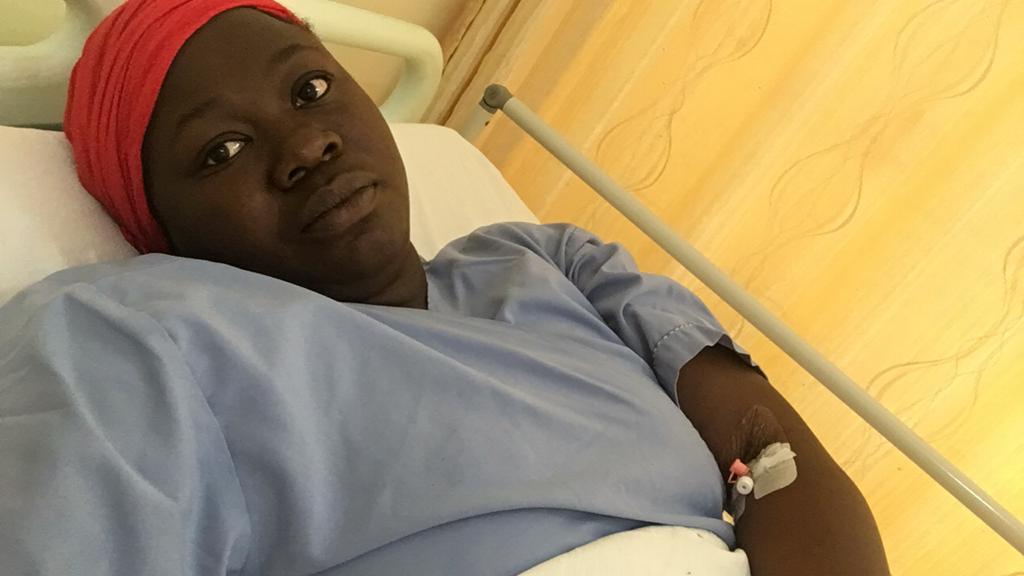

The doctor’s report showed that Eunice had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder and insomnia. She was put on treatment, which included medication and electroconvulsive therapy, which involves passing a carefully controlled electric current through the brain to relieve symptoms of severe depression and psychosis. As a result, she lost memory for nearly a week and could not recognise the people who visited her in hospital. Therefore, she couldn’t send thank you notes later. She also suffered other side effects such as confusion, nausea and fatigue.

She had taken the first step to recovery – seeking help – but she still had stigma to deal with.

“I became insecure – I was worried that people would label me ‘mad’. To hide what I was going through, I started posting funny memes on social media. On the other side of the screen, I was crying for hours in the privacy of my home. I didn’t want to go to work. I didn’t want to face people. I didn’t want to face reality. I became even more suicidal.”

After one attempt to end her life, the effects of an overdose had not worn off by the time her days off lapsed. She contemplated resigning from her job.

“One Monday morning, I called the human resources manager and told her I was quitting. She proposed that I see my psychiatrist first. I was admitted in hospital and put on suicide watch,” she said.

For nearly a month, Eunice found a home at the Chiromo Mental Health Hospital in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi.

At this point, her family didn’t know the full extent of her illness. As the breadwinner, she hid a lot of information from her parents. They were sickly and she didn’t want to alarm them or burden them with thoughts about her health. They only got wind of it when she was admitted in hospital the second time.

“I would withdraw from my son, but it wasn’t intentional. My absenteeism affected him, but I didn’t want him to see me at my weakest point.

“I tried to end my life several times. During my lowest moments, the only thing that came to mind was my son. This often stopped me … I am the only parent he has. It would be unfair to him,” said Eunice.

After a month in hospital, Eunice was discharged. She has since returned to work. She takes four medications every day – an antidepressant, a mood stabiliser, a sleeping pill and pain killers – and while she has had relapses, her family and friends offer a strong support system that helps her wellbeing. Her supervisors also understand when she reports late – they know the effects of the medication she is on weigh her down, and accommodate her needs.

Being vulnerable to her family and colleagues has lifted a bit of the burden of stigma off her chest, but not everyone is so understanding. She took a break from dating after she opened up about bipolar disorder, to a man who was courting her. He told her she was “crazy” and left her.

“I’m looking forward to a day when people will normalise talking about mental health to help reduce the stigma attached to it.”

Send your thoughts and feedback on this story to editor@africanwomeninmedia.com

We’re not gonna spam. We’ll try at least.

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Recent Comments