Groundbreaking Workshop on AI and Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence at AWiM24

Trending

Monday June 2, 2025

Trending

Read the full report here.

This report set out to research the barriers and obstacles faced by women journalists in sub-Saharan Africa, obstacles that hinder them from entering, progressing, and/or staying in journalism. Thus, the title Barriers to Women Journalists speaks to the varying types of obstacles experienced at various stages in their career. Whilst the report identifies a number of obstacles hindering women journalists, it also locates possible strategies, responses and interventions in addressing these. Therefore, the aims and objectives of this study are broken down into three research questions:

A mixed-method approach was used in carrying out the study, comprising of a questionnaire completed by 125 women journalists from 17 African countries, two focus group discussions, and six interviews.

Whilst there are several studies that aid in shedding light on gender inequalities in the journalism profession, Barriers to Women Journalists both fills a gap, and contributes to existing work in this field, by considering the following three forms of barriers hindering women in journalism:

In order to dispel suggestions that women enter journalism to pursue “the glamorous tube” (Emenyeonu, 1991), the first findings and analysis section begins with analysis of qualitative responses to motivation for women journalists. Analysis of our survey of 127 African women journalists across 17 African countries revealed a number of intersecting themes, namely passion, societal good, and women as role models.

The research into barriers faced by women journalists though understands that motivation and aspiration alone can only take one so far in an environment that is not entirely enabling. Ochieng’s (2017) research on women journalists in Kenya, found that women journalists are more likely to be judged by audiences and male colleagues on the basis of their appearance and personality traits rather than their professional accomplishments. In order to dismantle those barriers that exist, many studies have explored policies that would better protect women journalists. For example, in Jordan, the labour law stipulates “daily breastfeeding breaks, and appropriate daycare in companies that employ more than 20 women who together have ten or more children” (Najjar, 2013:425); however, within the private sector in particular, this practice has been difficult to monitor. Meanwhile, in Daniel and Nyamweda’s (2018) report, they found that in South African media organisations, there was a significant increase between 2009 to 2018 in gender policies that addressed representation of women in journalism through, for example, gender-balanced interview panels and fast-tracking policies.

South Africa has emerged as exemplar in gender equality in terms of leadership roles compared to other countries featured in our study. Daniels and Nyamweda (2018: 34) report on gender parity in South African newsrooms found that while not all media organisations have achieved the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development gender parity target of 50% by 2030, there was a 50/50 split across the 51 media organisations in their study (women 49%; men 49%; other 2%).

Gender equality in media leadership is important, and as this study reveals, can play a significant role in better organisational gender awareness, and implementation of women-enabling policies. Though, as this study will later discuss, this is often contending with dangers of tokenism and moral licensing. Nevertheless, a number of studies have examined the importance of the role of women in decision-making positions in newsrooms, moving away from past notions of “ideal” job roles for women being garnered towards care-giving roles (Peebles, Ghosheh, Sabbagh and Darwazeh 2004:24). These types of societal positioning of women, and deeply ingrained cultural stereotypes of women, are key factors in the barriers to entry, retention and progression of women journalists in sub-Saharan Africa. They have come to manifest in gendered role assignments in the newsroom where women are more often considered for so called soft news of health, fashion, development stories, as opposed to the ‘hard-news’ of politics and business. This inadvertently also leads to gendered allocation of resources as this study later reveals.

Other research has revealed various other gendered experiences of women in media, from blaming women for their experiences, as was found by Melki and Mallat (2016) in their in a study into why women journalists in Lebanon were being marginalised. They found that respondents, from various levels of hierarchy, blamed women journalists themselves for making the glass ceiling harder to break by taking ‘safer’ roles when they got married or had children. Similarly, Blumell and Mulupi (2020a) examined sexism in the newsroom in Kenya, South Africa and Nigeria and found “sexual abuse, sexual harassment, unfair job allocations, limited access to power, unfair pay, and overall unsafe work environments as significant problems”.

In executing this study, and to answer the three overarching research questions, a mixed-method approach was employed. The first stage was the distribution of a questionnaire. The questionnaire asked a combination of demographic, closed-ended and open-ended questions. The latter being useful in gathering qualitative responses through which responses to closed-ended questions might be tested. Such qualitative responses were then analysed using grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) to tease out the emerging themes. The theming process went through three stages of coding: open, axial and selective. From this, a reflective narrative was constructed. Where appropriate, graphs and charts were captured from closed-ended and Likert Scale questions , alongside the analysis of the narratives shared.

The analysis of the questionnaire led to the identifications of key topics to be tested during interviews and focused groups. Six semi-structured interviews were conducted between 10 and 16 September 2020 with participants from Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. While care was taken to invite participants from a range of countries, several did not show up. The interview questions focused on the types of barriers faced by women journalists, pay gap, forms of discrimination, gendered role assignments especially in technical roles, being the sole female in a newsroom. All interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams, recorded and transcribed.

Two focus groups were carried out. The first had six participants from Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, South Sudan and South Africa; and explored a range of themes that emerged from the questionnaire analysis, within a solutions and best practices framework. The second focus group had three participants (eight were invited) from Botswana, Rwanda and Uganda. This focus group explored the themes that emerged relating to gendered role assignment, and also employed a solutions and best practices framework. It is notable that a focus group on sexual harassment was organised, but none of the participants showed up for the scheduled meeting. This perhaps further speaks to the difficulties in both speaking about sexual harassment and the challenges faced in tackling it. All focus groups were conducted via Microsoft Teams, recorded and transcribed. No prior contact was initiated between participants.

Given the sensitive nature of the study, respondents have been annonymised throughout this report. Where the report uses direct quotes, for the most part the country and position of the respondent was used to illustrate the geographical spread of the experiences. Where the quotes were particularly detailed and risk of identification is greater, no geographical or position information have been provided.

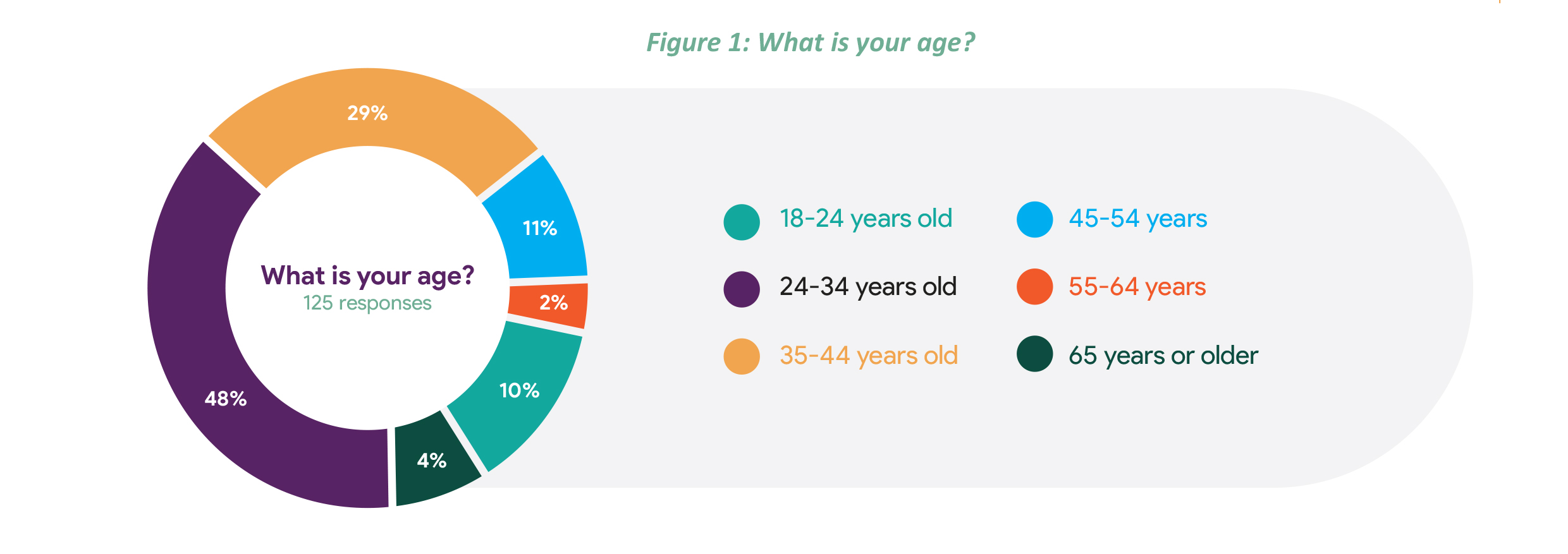

The majority respondents were from East African, while respondents from West Africa were the second demographic to participate in the research. Respondents’ age was wide ranging, with 48% from the 25-34 age group, 28% were 35-44, and 11% were 45-54; leaving the rest of the respondents in the 18-24 and 55-64 age brackets.

Figure 1: What is your age?

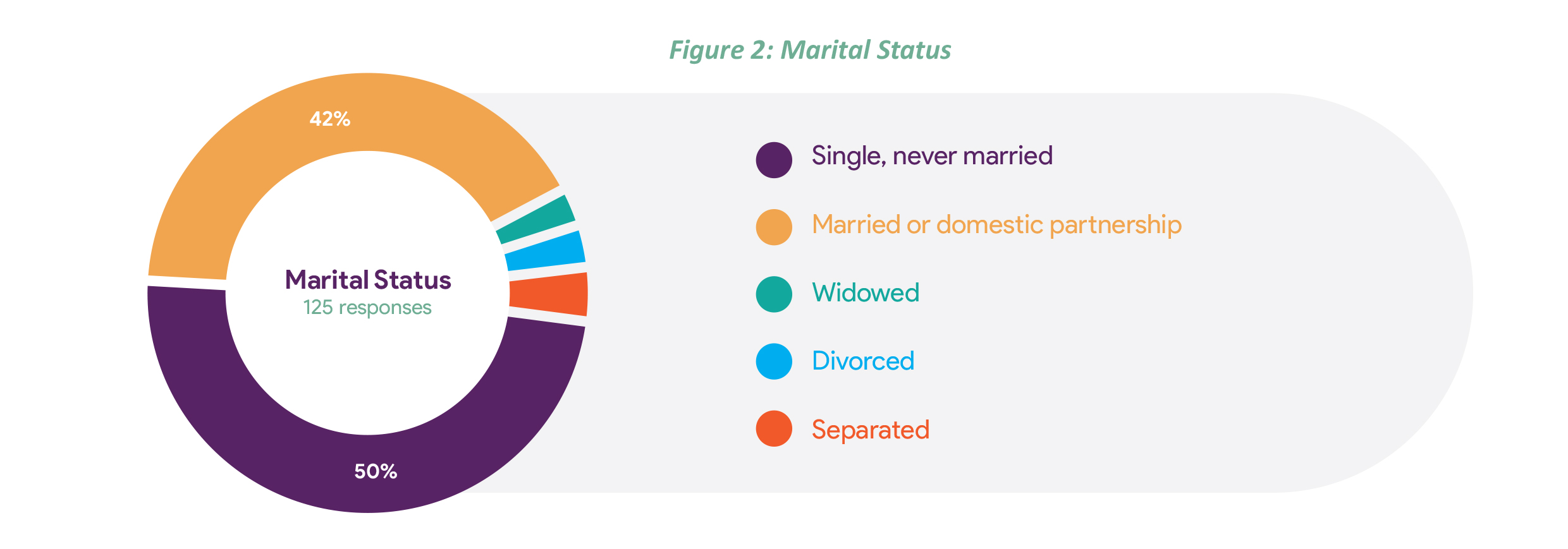

We collected data on marital status and children due to suggestions that these often interfered with career progression of women journalists. Almost half of the respondents were single, while 41% were married. A large majority had children.

Figure 2: Marital Status

Figure 2: Marital Status

Figure 3: Do you have children?

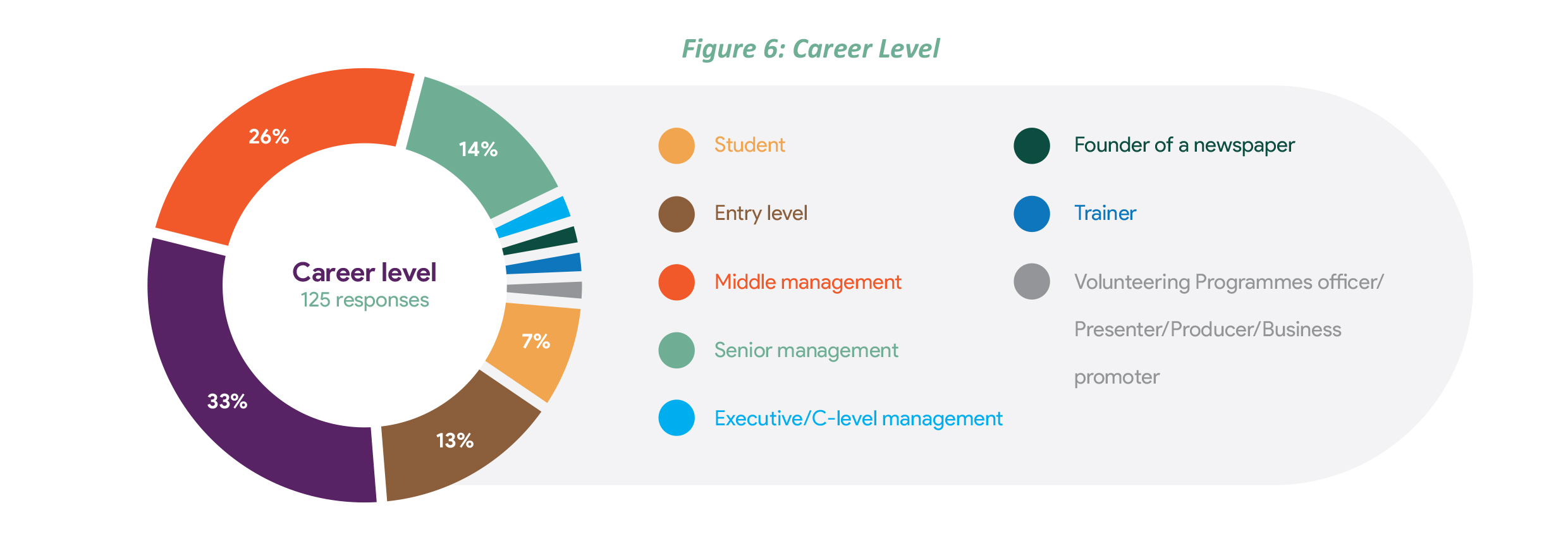

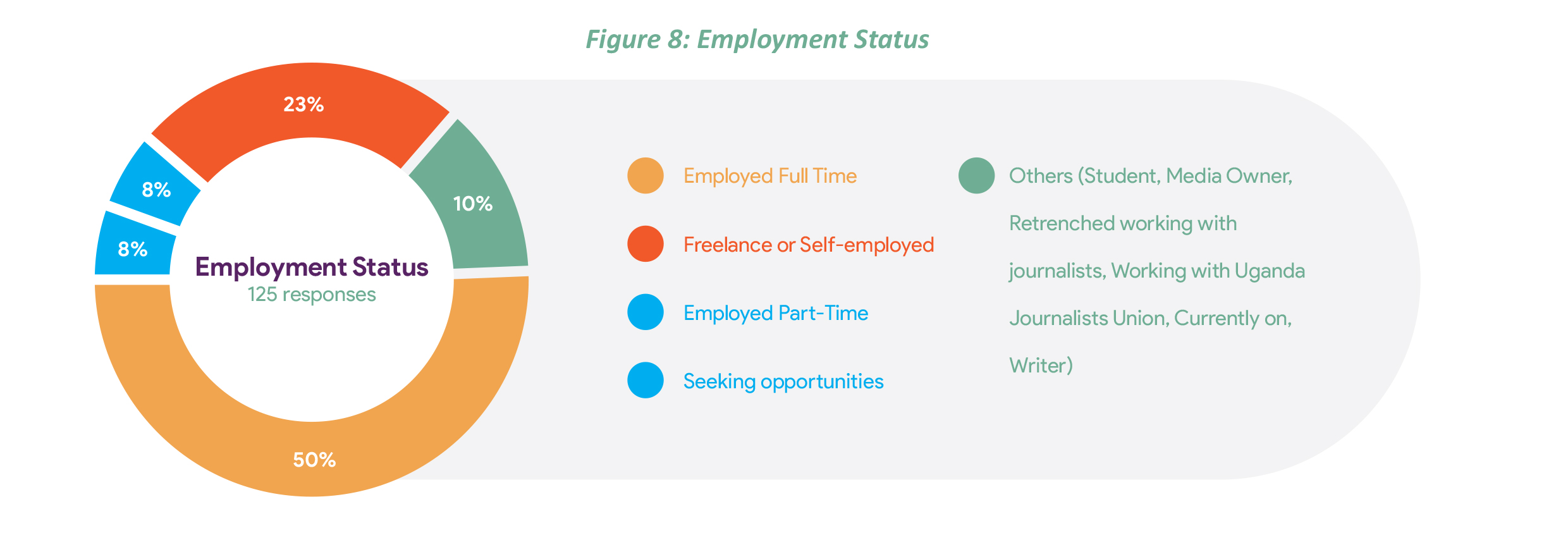

Levels of education were widely spread, and a majority of the respondents were either in mid-career level or middle management; while a majority of respondents were in full-time employment.

Figure 4: Education

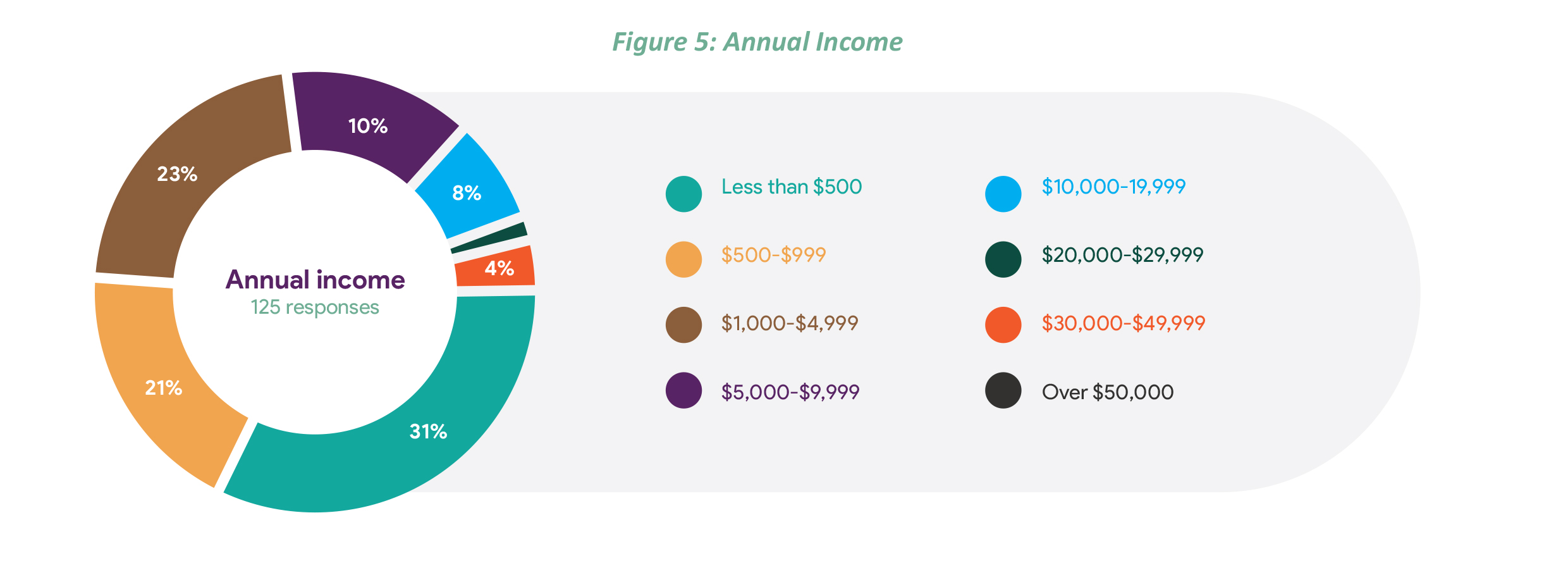

One area that consistently emerged as a point of contention amongst the participants was salary disparities. The geographical locations of salary disparities were an interesting find. A majority of respondents said they earn less than $500 per annum from journalism. Of these women, 15% were from West Africa, the majority of which were in Nigeria. All respondents that made up the 15% in Southern Africa earning less than $500 per annum from journalism were from Zimbabwe. East African respondents, however, made the majority in this category with 69%, represented by Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, South Sudan and Zambia. Overall, 25% of those earning this amount said they were in full-time employment and from Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda and Tanzania, and 25% were freelance.

Figure 5: Annual Income

Comparably, 23% of respondents said they earn $1000 to $4,999 per annum. Most of the respondents were employed in part-time/full-time roles or were freelancers/self-employed and across career levels. In terms of location, participants in this category were primarily from South, East and West Africa (Zimbabwe, Uganda, Tanzania, South Africa, Rwanda, Nigeria, Malawi, Kenya and Ghana).

Figure 6: Career Level

Figure 6: Career Level

Those earning $10,000 to $19,999 per annum were across all middle level/middle management/senior management career levels and primarily in full-time/freelance job roles from Southern, East, and West Africa (Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda). Comparably, there was one respondent from Nigeria earning $20,000 to $29,999 and working in middle management whilst studying.

Intriguingly, there were some respondents primarily in full-time employment, middle level, middle management, senior management and executive management roles earning $30,000 to $39,000. There were just a couple of persons in this category who were working in a freelance or self-employed capacity. All of the persons in this category were from East and West Africa (Rwanda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and Kenya).

Figure 7: Location

Figure 8: Employment Status

This report has been organised according to the themes that emerged from the data analysis. Section one focuses on motivations and aspirations, while section two expands on the five themes that emerged from the analyses of experiences shared in relation to barriers of entry and maintenance of the journalism careers of the 125 women journalists who participated in the study.

Section 1: Motivations and Aspirations

In analysing the responses offered to describe motivations and aspirations for entering journalism, the words ‘passion’ and ‘love’, were used to convey the emotive connection respondents attach to their role as journalists.

When it came to passion, the most commonly used terms in describing motivations and aspirations were a calling, love for the craft, advocacy, and early influence. The love for storytelling was a prominent response, and for the most part, this type of enthusiasm was used to describe a commitment to positively impacting the lives of others. Respondents appreciated the position of journalists as mediators of information.

This sense of wanting to impact the lives of others by telling their stories, spilled into other desires to perform societal good. Advocacy was therefore a predominant response, and overall responses relating to societal good can be categorised into three dimensions of advocacy interests: (1) being a voice for the voiceless, (2) initiating change, and (3) fostering fairness.

Several key figures were identified as sources of inspiration. While these were largely motherly figures, some were encouraged by male relates too. In contrast to some previous research suggesting a desire for the glamour of journalism, respondents who pointed to gaining inspiration from seeing other women journalists, like Catherine Kasavuli, Oprah Winfrey, and the late Rosemary Nankabirwa, spoke largely of admiration for the skills and knowledge displayed by these women.

The study also found that because respondents followed the advice of their early role models or mentors, in pursuing journalism and mass communication programmes, they were able to develop a number of useful skills for the journalism world of work. For example, 53% of the respondents spoke mostly to the skills developed that helped them navigate their career path, such as the ability to negotiate salaries, career planning, and general preparedness for their role as journalists.

Experiences entering the industry into the roles respondents aspired to showed an almost equal footing between those who were able to enter the role they aspired to, and those who were not. Those who were unable to enter into the aspired roles, either changed their goals, are still climbing the ladder or remain unemployed. In narrating their experiences of applying for the role they aspired to, less than a quarter of the respondents described their experience as good or fair.

The main emerging themes surrounding barriers for women in journalism found in this study were:

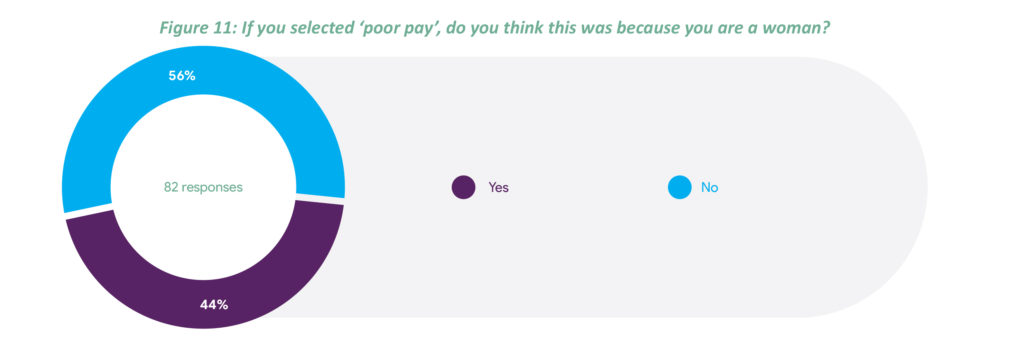

The experiences shared by participants in relations to poor pay demonstrated the many faces of gender pay gaps. Gendered allocation of opportunities for training, gender-role assignment, and a lack of transparency in promotion processes emerged as key factors that lead to gender pay gaps. Several respondents felt their male colleagues were more likely to be supported to attend trainings and conferences than female colleagues. The issue of transparency and clear promotion processes have led to participants either getting promotions but still with lower pay than their male colleagues on the level. On the other hand, their lack of opportunities for training, and experiences of gendered roles and allocation of resources to do certain kinds of stories, have limited the opportunities of respondents for progression, which inadvertently leads to job and salary stagnation. It is not surprising then that a whopping 65% of respondents said poor pay has had the most negative impact on their career progression, with 43% attributing their experience of poor pay to gender bias.

Figure 11: If you selected ‘poor pay’, do you think this was because you are a woman?

Disparities between men and women in the distribution of job roles

The ‘soft-news’ versus ‘hard-news’ spectrum emerged in shared experiences of gendered allocation of roles and resources. This generally meant that respondents were often assigned to report on roles considered ‘women topics’, relating to health, entertainment, fashion, among others. The lack of gender balance in leadership roles further added to this, and respondents felt they had been discouraged from aspiring to editorial leadership roles, from taking technical roles, like camera operating, and from reporting certain types of stories, like those that required entering environments of conflict or protest. In some cases, marital status was weaponised for discrimination, with some respondents sharing experiences of being told by their managers that because they were married, they could not take up technical roles.

Figure 14: At what stage in your journalism career have you experienced barriers of entry?

Sexual harassment was the second most shared experience by respondents. The perpetrators were as wide ranging as the nature of the sexual harassment experienced. From suggestive propositions for a sexual relationship in exchange for work, to online sexual harassment and physical assault including, in one case, aggravated assault at gunpoint. Experiences shared also demonstrated sexual harassment happens at all points of career stages from the point of recruitment, where sex for work was commonplace, to harassment by sources, colleagues and superiors. Sex for pay again presents another face of the gender pay gap, with several respondents sharing experiences of having to contend with sexual advancements of superiors in exchange for a salary increase. In terms of dealing with such experiences as sexual harassment, sexual corruption and sextortion, many respondents felt they simply had to grow a tough skin, while the narrative shared by others in some instances suggested a lack of awareness of what constitutes sexual harassment and of sexism. For the latter, the visibility of sexism was used as valuation on the extent to which it exists.

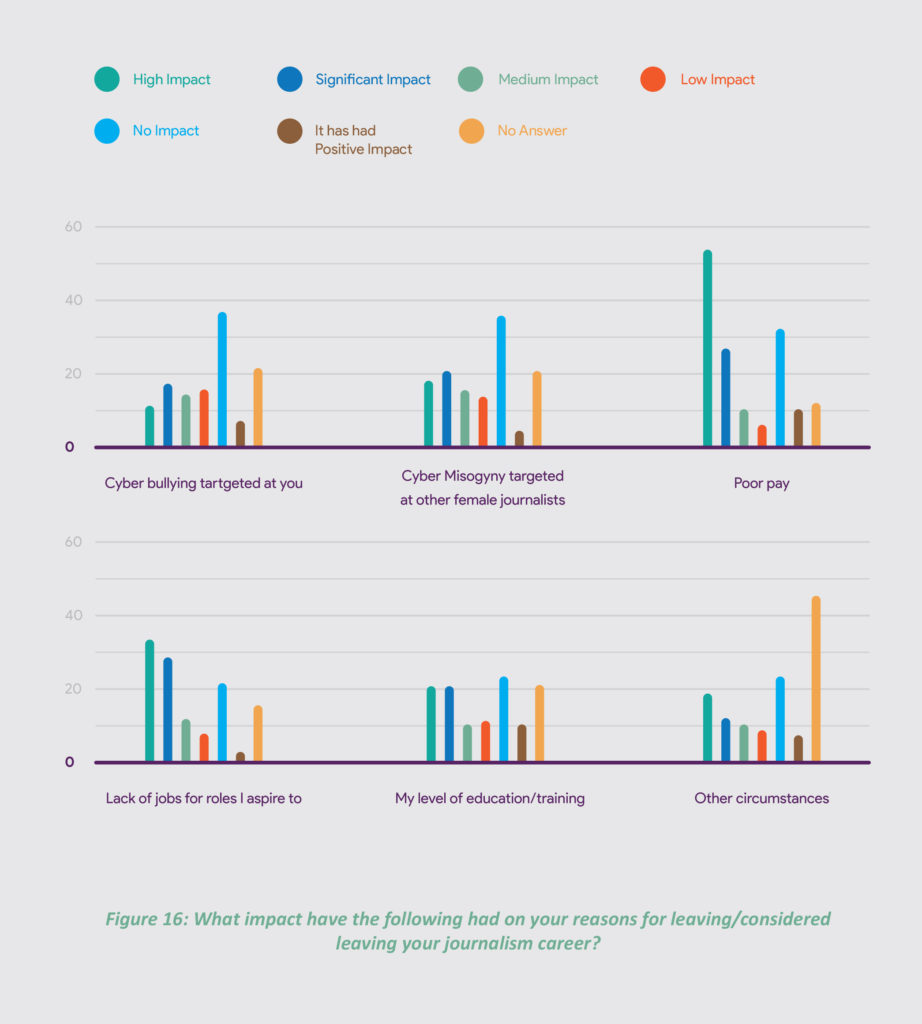

Bullying emerged within the newsroom and online, perpetuators were both men and women, and online from audiences. For respondents, the experiences of cyberbullying and cybermisogyny has led them to have low self-esteem, and to a fear of social media.

Respondents from South Africa were the only ones to share experiences of racial discrimination, though respondents from other countries shared experiences of discrimination relating to ethnic group differences.

Of the 41% of respondents that were married/in a domestic partnership, only 33% said this status had an impact on their entry into journalism, and only 7.2% said it impacted their career progression. Furthermore, only 12% of the 20% of respondents that have children, said this negatively impacted their career progression. Nevertheless, societal impacts on the experiences of respondents in relation to being married and/or having children, ranged from having to slow down career progress to focus on family and childcare needs; the sexual harassment of women in media considered ‘loose’ because they work in media, and the varying faces of missed opportunities. Experiences with employers ranged from a lack of policy consideration for childcare responsibilities, while also using childcare responsibilities as a reason to limit the progression and opportunities for women journalists in the study.

The many faces of gendered pay gap also come in under family life, with some examples given by the interviewees of this study highlighting practices of employers paying men more because of their assumed familial breadwinner role. The impact of societal attributions of gender roles and such cultural perspectives have also been described as leading to gender-based discriminations in the workplace, with male colleagues and superiors who maintain such perspectives in their interactions in the newsroom.

The issue here is the extent to which organisations are gender-conscious enough to, firstly, be flexible to adjust to the needs of parents, and secondly, not letting it impact promotion, or rather having a more gender-conscious approach to work allocation and promotion, that is considerate of these societal allocations of roles. Maternity policies, women mentors among others, were also considered to be examples of how challenges relating to family life and work can be addressed.

“At this stage I was married and bore a child. Yes, when married responsibilities are increased more challenges come in your way. The point is I am working towards a successful career, but people tend to think that you can no longer give much attention to work and they also make some decisions for you based on your status without consent. For example, when pregnant, your employers may not recommend you for some training or other opportunities just because they think it is too demanding… There are also opportunities given to unmarried females, like some training trips outside town that required them to spend one or two nights away, but not grant them to you because they think you can’t leave your husband. The point is they think and decide on our behalf without our consent or any comment.” – RWANDA, MIDDLE MANAGEMENT.

The politics of equity versus quota comes to play in experiences of women in media leadership positions. Respondents described the promotion of women to leadership position for the purpose of outward appearances, without attaching the promotion with the necessary equity to have impact. Such tokenistic gesture also appears to place the burden on the few women promoted to leadership, to ‘prove’ that women can lead. Thus, the call for more transparent and gender conscious approaches to leadership, come with a call for a deliberate process that allows a funneled career development towards leadership. Such a process, where accompanied with adequate training and wider organisational gender awareness, it is argued, will make attainment transparent, and can lead to a more balanced representation in leadership. Such a deliberate organisational cultural shift can also go a long way in improving representation and voices of women and women’s issues in media content.

Figure 16: What impact have the following had on your reasons for leaving/considered leaving your journalism career?

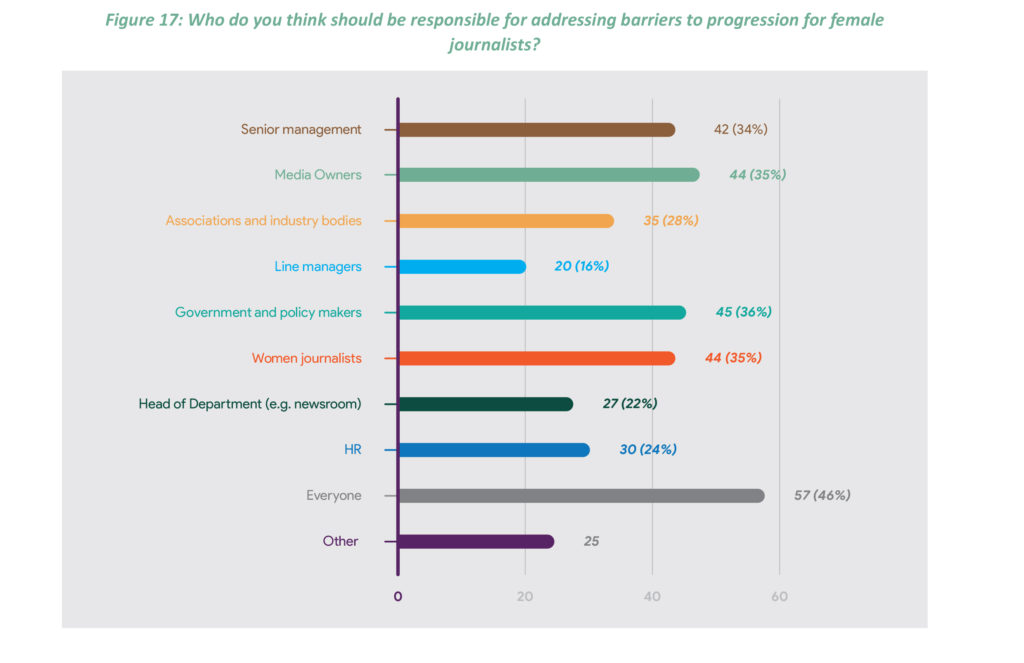

When asked who was responsible for addressing barriers to progression of women journalists, a majority of the respondents said everyone is responsible. Other respondents were of the view that government and policy, media owners, women journalists, senior management, associations and media bodies, human resources departments, heads of departments, and line managers should all be held accountable in addressing the barriers that women journalists encounter. The collated responses demonstrated that all stakeholders are a part of the solution. However, the question we are left with is whether the stakeholders outlined above are ready and willing to make that change?

Who do you think should be responsible for addressing barriers to progression for female Journalists?

From the experiences of respondents, the reality appears to be that most have taken and are forced to take individualised approaches to dealing with the challenges they face. Participants of the focus group on solutions, for example, highlighted the need for women journalists to take an entrepreneurial approach to both skilling up and using their skills as a way to combat the issue of job security. However, the notion of individualised women’s empowerment, that places the responsibility on the woman journalist herself, has the danger of missing the barriers beyond the control of the women and assumes only that it is because the woman is not hard-working enough that she has these experiences.

Such notions, and all the experiences shared in this study, demonstrate the need for training on gender bias, and for this to come much earlier in the career of all journalists, male and female. Participants suggested that journalism course contents should include gender-conscious to tackle the biases and barriers discussed in this report, which include sexual harassment, bullying, sexism, among others. Media houses and managers would also benefit from courses on the development and implementation of gender policies.

Indeed, gender policies and maternity policies, were mechanisms mentioned at several points in the study that can help to set organisational standards and transparent processes. While, however, South African newsrooms appear to have found this a useful mechanism through which gender balance in media leadership has been achieved, other respondents suggest they have had less success in their countries. For the most part, it is not simply a question of having policies, but the politics of implementation.

AWiM and Fojo hope that this study will contribute to the creation of enabling environments for African women who work in media industries, and change the way African women are represented in media content. The findings of the study, and recommendations presented above, could be starting points for the various stakeholders to take positive action by designing activities and interventions that will effect lasting change. Training, capacity development, mentoring, development and implementation of policies require a joined-up approach, sustainable funding and a willingness to move beyond tokenistic gestures.

We welcome further research at regional, national, and organisational levels, and encourage collaborative and supporting efforts between organisations. We particularly encourage more research that looks at the ways in which women journalists are mobilising and actively addressing the challenges they face in the industry. Such research will further empower women as active change-makers in the profession.

We’re not gonna spam. We’ll try at least.

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Copyright 2020. African Women In Media

Recent Comments